Resurrection themes in Colin McCahon’s art

I think Colin McCahon would have been at home at Cityside. He was a thinker, contemplative, obviously artistic and not one to follow the crowd. He was painting pictures about Jesus at the same time as Andy Warhol was painting Coke bottles. He painted them in a way that attracted scepticism and derision from the general public, offending the sensibilities of Christian and Non-Christian alike. But—and don’t take this the wrong way - perhaps the characteristic that would have made him most at home at Cityside was his doubt. His paintings are testament to the fact that he is a faithful doubter, so much so, although his body of work deals almost exclusively with Christian themes he felt so humbled by his doubts, he was unwilling to call himself a Christian. Yet, as I think you’ll see —his paintbrush reveals a deep and searching faith.

McCahon’s was nostalgic for the era when art was believed to have real power for ordinary people—in his words “signs and symbols for people to live by”; a time when paintings brought to life Biblical stories and concerned themselves with the mysteries of faith. Today we are going to explore the signs and symbols in several of his paintings that deal with the theme of resurrection.

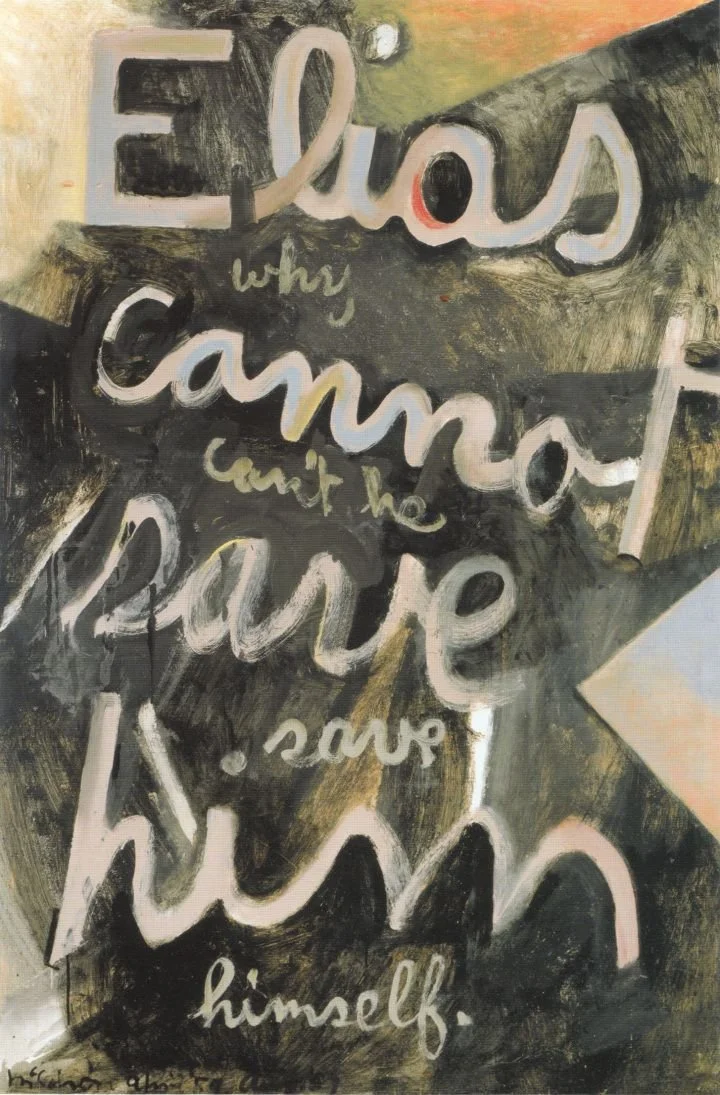

In 1959, McCahon produced a number of paintings on the theme of Christ’s crucifixion and resurrection, and in particular the moment on the cross where he calls out to God (“Eloi”) but is misunderstood to be calling for “Elias”(-the prophet Elijah-) by the crowd. Consequently, these paintings are known as the Elias series. Here’s one of them, just for context:

Elias: why cannot he save himself (1959)

This is a typical work from this series. Another common feature of the paintings in this series is their use of words, words that interrupt the seeing by demanding to be read. McCahon explained his fascination with the written word came from watching a signwriter at work on a shop window as a child. He describes it using a religious allegory: “I was watching from the outside as the artist working inside separated himself from me (and light from dark) to make his new creation”. ‘The word’ is also an important metaphor in the Bible – John tells us that “In the beginning was the WORD, and the word was with God.” McCahon’s increasing use of words over images in his art helped him on one hand communicate more directly with his viewer, but also created ambiguity.

Such as in this work, where the arrangement of the words creates multiple meanings. We can read, “Elias cannot save him”, “Elias, why can’t he save him?” or putting together the large and small letters, “Elias cannot save him; why can’t he save himself?”. How is it that the almighty God cannot save himself – how can we be expected to believe in such a God? The dark palette used for the many of the Elias works reflects a sombre mood of doubt.

However, there are two paintings in the Elias series that offer a glimmer of hope.

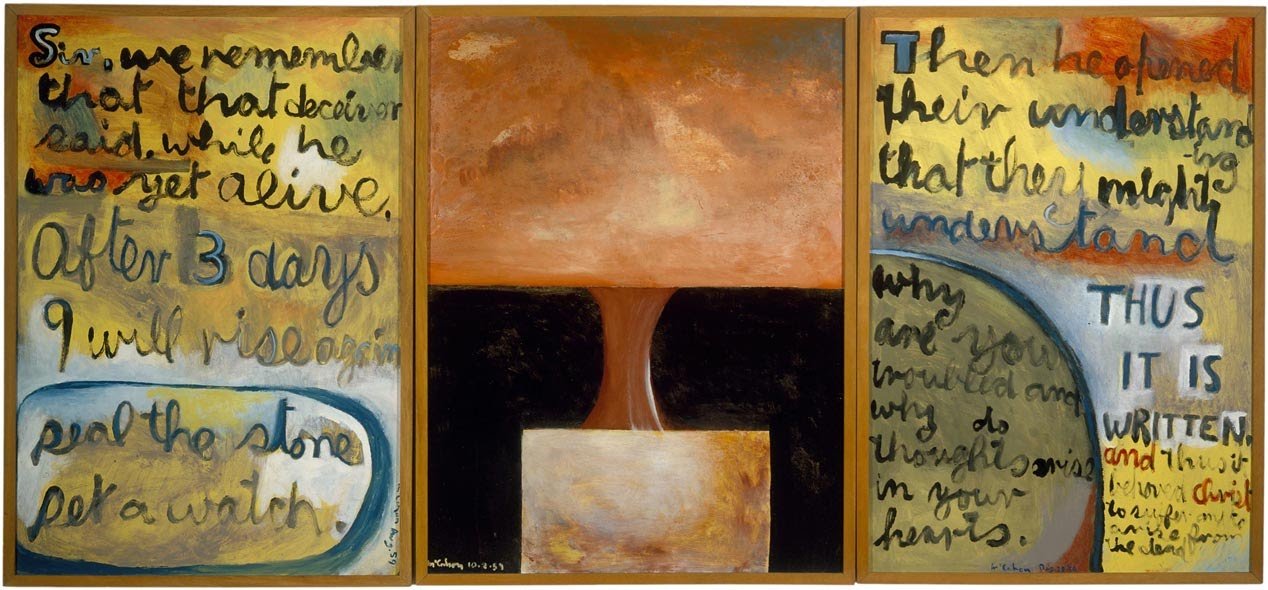

Elias Triptych: Seal the Stone – Red, Black and White Landscape – Thus it is Written (1959)

His Elias Triptych has the 3-part structure common to religious altarpieces from the era of Christian art McCahon so admired. The central panel represents the resurrection in an abstract form: from the white tomb springs blood, a symbol of Christ’s promise of redemption. This flows into the blood-red sky, which hums and vibrates with divine energy.

This is offset by two side panels that visually mirror one another but contain contrasting sentiments. The left panel quotes the words of doubt from the chief priests and Pharisees: “Sir, we remember that that deceiver said, while he was yet alive, After 3 days I will rise again.” And Pilate’s reply: “Seal the stone, set a watch” – fittingly sealed inside a stone shape.

In contrast, the right panel contains Christ’s words and the gospel writer’s. In the rounded shape, a kind of thought bubble or maybe the edge of the stone, just rolled away, are Christ’s words “Why are you troubled and why do thoughts arise in your hearts?”. In other words, Why do you doubt? The background paintwork is appropriately murky, almost obscuring the words.

But this time, there is hope and revelation, present also in the use of yellows and rich reds in the outer part. “Then he opened their understanding, that they might understand. THUS IT IS WRITTEN… (capitalised with the authority of a divine act) and thus it behoved Christ to suffer and rise from the dead.”

These words come from Luke 23 where the resurrected Jesus appears to his disciples and tells them that he is the fulfilment of the prophecies in the Old Testament. [SLIDE] Here is the text from another translation: “Then he opened their minds to understand the Scriptures, and said to them, ‘Thus it is written, that the Christ should suffer and on the third day rise from the dead, and that repentance and forgiveness of sins should be proclaimed in his name to all nations, beginning from Jerusalem. You are witnesses of these things.”

The last part of that verse is the title of another work in the Elias series, produced in the same month.

You are witnesses (1959) 1609 x 422 mm Enamel on Hardboard

This painting takes the form of a long vertical panel – like a prophetic scroll or the form of a human messenger who directly confronts the viewer with the powerful declaration: “HE IS RISEN. You are witnesses of these things. He is risen from the dead.”

The Panel has three sections.

The top portion appears to be a misty landscape where the capitalised words HE IS RISEN in white rise from the land, as if they are alive. These words come from Matthew 28.6 where an angel speaks to a woman in the garden, which is perhaps represented in the swathe of green. Christ’s resurrection is like a sunrise in the misty morning landscape, signalling the dawn of a new age.

The words “HE IS RISEN” are repeated like a refrain in the lower portion. The additional phrase, “FROM THE DEAD” reinforces the miraculousness of the event. The black patch at the bottom suggests the apparent finality of death, but from the gloom comes light… with the word RISEN outlined so it almost appears 3D. In fact, we can also read a resurrection visually in the painting from the lowest to the uppermost portion, from the dark tomb to the mystery of the supernatural light in the central portion to the defiance of the white letters standing on the earth in the top portion. Like the Elias Triptych, three portions: three days and Christ rose from the dead.

The middle portion squarely addresses the viewer with the bolded word YOU. YOU are witnesses of these things. These words also come from Luke 23, the verse quoted earlier.

That McCahon also titled this painting, “You are Witnesses”, underlining their significance. As Stu said to me when we spoke about this last Sunday, if there are no witnesses, is there a resurrection? ……. And is meant by a witness? In one sense, the disciples were witnesses, who had first hand experience of Christ’s life, death and resurrection. However, a second sense of the word is “evidence” as in something or someone acting as witness to the fact. And I think this is McCahon’s challenge to the spectator. What does it mean to be a witness to the Resurrection? What might it look like to embody evidence of the Resurrected Christ: the hope of wholeness that is present in suffering and brokenness?

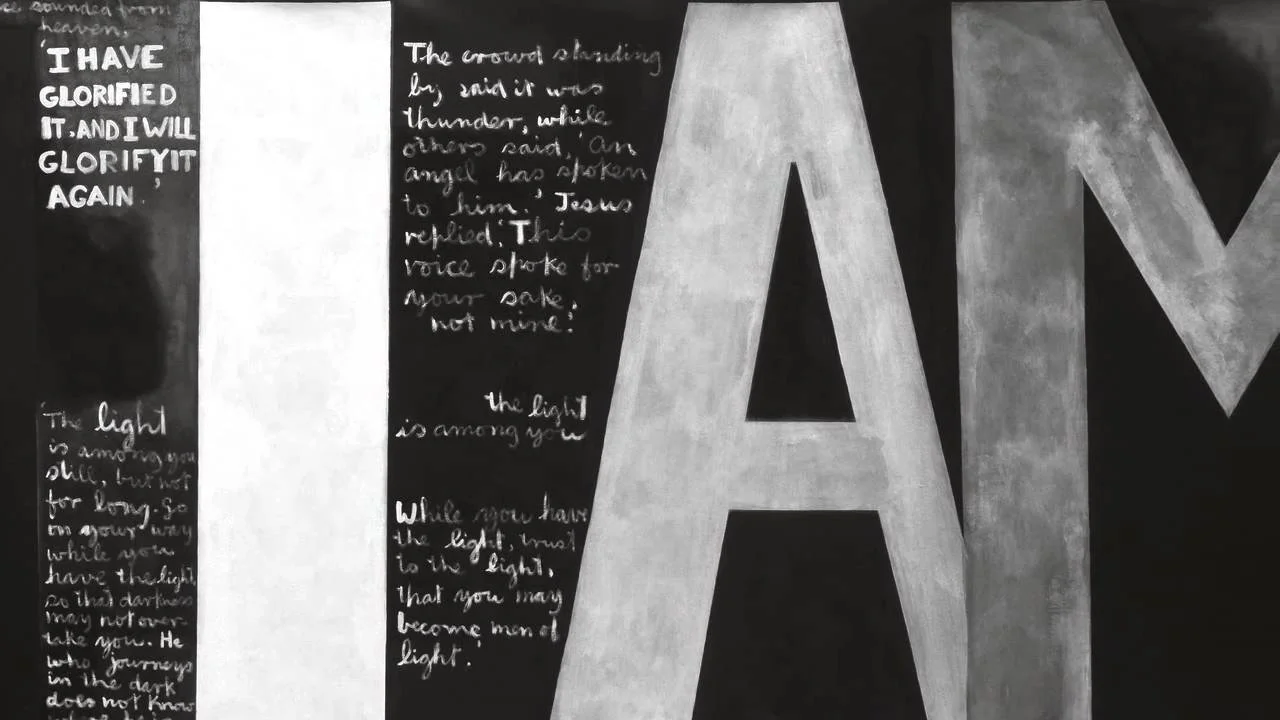

Victory over Death 2, 1970. Synthetic polymer paint on unstretched canvas, 2075 x 5977 mm.

The final painting I’d like to discuss today is a classic McCahon, one that you may have seen at the Australian National Gallery in Canberra. It was made 11 years after the two previous paintings and is on a much larger scale. This work is almost 6 metres long and 2 metres high, about twice the dimensions of the Elias triptych. On raw, unstretched canvas, painted thick with black, are scrawled passages from scripture, like a chalk message on a divine blackboard. They are dominated by the gigantic words I AM.

The work is called “Victory over Death 2,”and for me, there is something very cathartic about the undeniable presence of God implied by the towering I AM. The meaning comes as much from these monumental forms as the words themselves. They reflect the artist’s inability to represent God’s likeness with an image. In Exodus, when asked by Moses what he should tell the Israelites if they ask his name, God answers, “I AM; that is who I am.” I am is emblematic of the essential mystery of God and calls to mind all the great “ I am” statements from John’s gospel: “I am the way, the truth and the life” – (quite literally the way, as we walk past this massive painting) ,“I am the light of the world” and “I am the resurrection and the life.” The giant white letters of I AM is the victory over death, the resurrected Christ in our midst, and we are the witnesses.

However, what is less visible is the word AM in black paint in front of the I, mirroring the white letters after them. So we get: AM I AM, or AM I? I AM. Am I am sounds like a meditation chant, it suggests the eternal presence of God and the divine mystery. “I am who I am.” But read as a question, Am I? I am – is ambiguous. Does it relate to Christ, to God the father or McCahon himself? McCahon said that in 1959, the year he painted the Elias series, he became “interested in men’s doubt” and admitted “these same doubts constantly assail me too… I believe, but don’t believe.” Of ‘Victory over Death 2’, he said “Doubts come in here too.”

The smaller text in white overlaying the black AM refers to the the gospel of John where Christ predicts his death and says: “‘Now my soul is in turmoil and what have I to say? Father, save me from this hour.” McCahon omits the punctuation as he often does, which in this case is a question mark after ‘hour’. This gives the phrase greater ambiguity. Rather than appearing as a rhetorical question, “Will I say, Father, save me from this hour?” it becomes an imperative: Father, Save me from this hour. However, it is quickly followed by: “No, it was for this that I came to this hour ‘Father, glorify your name.’ Read this way, it recalls AM I? I AM.

At the top of the second column, we read: “A voice sounded from heaven (and in bolded white CAPITALS as God speaks) ‘I HAVE GLORIFIED IT, AND I WILL GLORIFY IT AGAIN.’ God’s words are positioned right by the central I – bright, white, source of heavenly light, at the intersection of doubt and faith, darkness on the left and light on the right, as if between two poles of doubt and faith just as in the Elias triptych.

Half way down we read, ‘The light is among you still, but not for long’. “The light” or the risen Christ may be seen to be present in the bright figure of the “I”. That the light will not be with them for long is reinforced by the sense of fading light in the large M. “

The phrase “the light is among you” is repeated halfway down the third column. Again, another flash of hope. Under this is scrawled, “While you have the light, trust to the light, that you may become men of light”. For me this seems to parallel the words, “You are the witnesses” in the previous painting. The God-light needs men and women to trust to the light, to continue to be the light. And finally, underneath the M there are the words: ‘My way is Known to you.’

McCahon knew the way of suffering and the loneliness of being an outsider. He felt misunderstood and underappreciated as an artist and was openly mocked in the media. The gift of this work to the Australian government for that country’s bicentenary in 1978 provoked a storm of controversy in parliament and the wider public. One newspaper even suggested the gift was “Muldoon’s Revenge” on the Aussies. McCahon said of this period that it was a “slow burning hell.” The state of McCahon’s faith in his final years is a matter of debate. What we do know is he drank heavily, probably to numb his despair, he lashed out at those closest to him and his paintings got darker. (His final painting is called “I considered all the acts of oppression.”)

McCahon said his painting was “almost entirely autobiographical.’ It was a kind of therapy for him, in his struggle with faith. However, his paintings also offer therapy for us as well. Philosopher Alain de Botton has argued for this concept of “art as therapy.” Art works can help us to recognise our common humanity, offer us moral lessons and allow us to meditate on the meaning of life. Colin McCahon’s art does this. Half a century on they are “signs and symbols” that still speak of the mystery, stir the soul of the spectator, and shine light into dark places.

References:

http://www.nzedge.com/legends/colin-mccahon/

R. Forward. ‘McCahon: Talking to Himself.’ McCAHON: TALKING TO HIMSELF, Colin McCahon, Victory over death 2, 1970, by Roy Forward, National Gallery of Australia Research Paper no. 49

G. Brown. Colin McCahon: Artist.