Jesus is stripped of his garments

Golgotha

In approaching the 10th station in the series of 14, we locate Jesus at Golgotha. Golgotha is Aramaic for “the skull.” Calvary is the Latin form of the word. Scripture does not reveal the precise location of Golgotha. It simply states that Jesus’ crucifixion took place near but outside the city of Jerusalem.

We also know that this event also occurred near a well-traveled road, as passersby had the opportunity to mock him. It was common practice for Romans to select conspicuous places by major highways for their public executions. As this crucifixion was visible from a distance it is also likely that it took place on a hill. The image you see is the commonly accepted location of Golgotha.

The gospel reading that relates to this station can be taken from Mark’s gospel, chapter 15:

Mark 15:22-26 The Crucifixion of Jesus

22 Then they brought Jesus to the place called Golgotha (which means the place of a skull).23 And they offered him wine mixed with myrrh; but he did not take it. 24 And they crucified him, and divided his clothes among them, casting lots to decide what each should take.

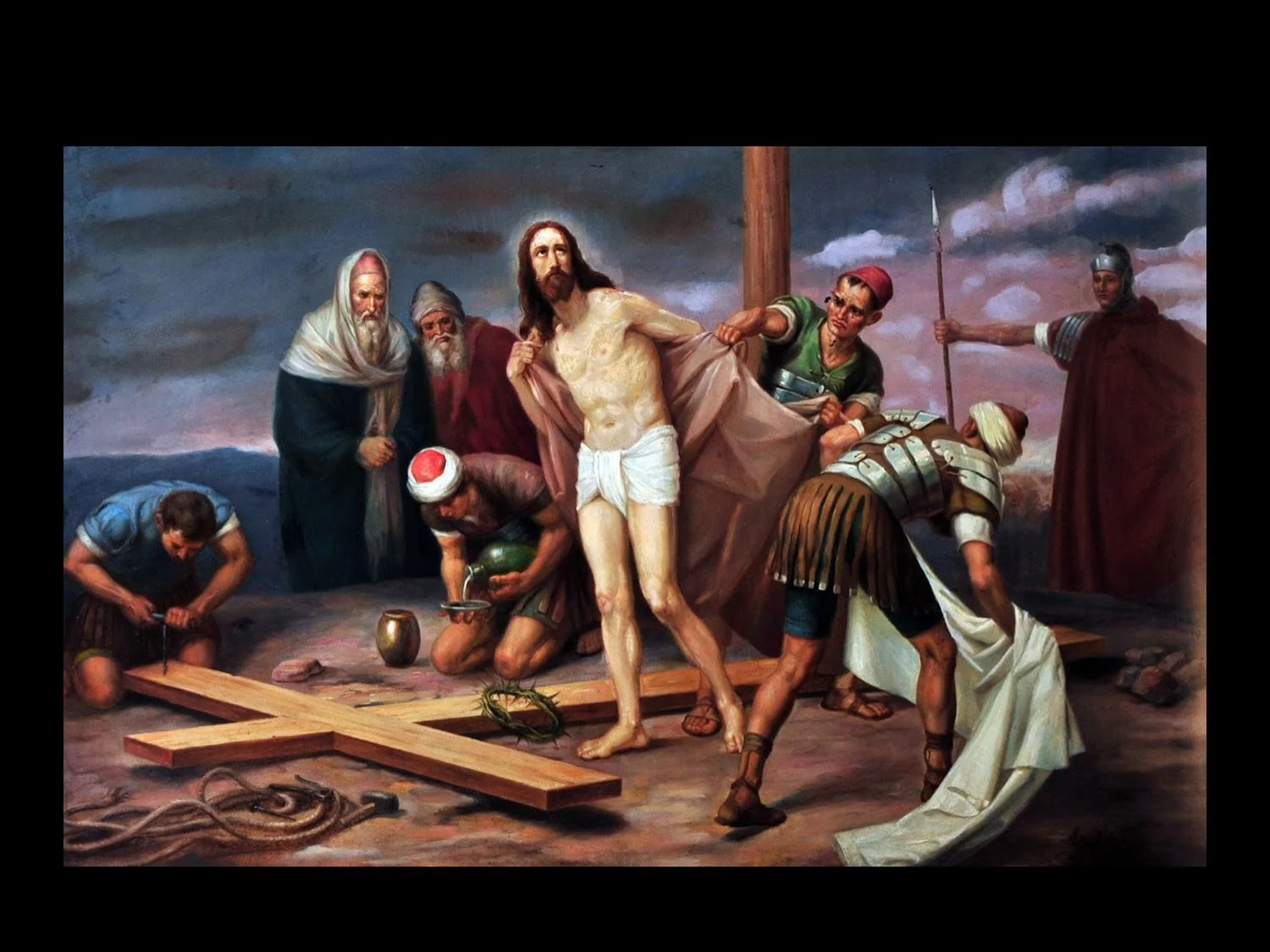

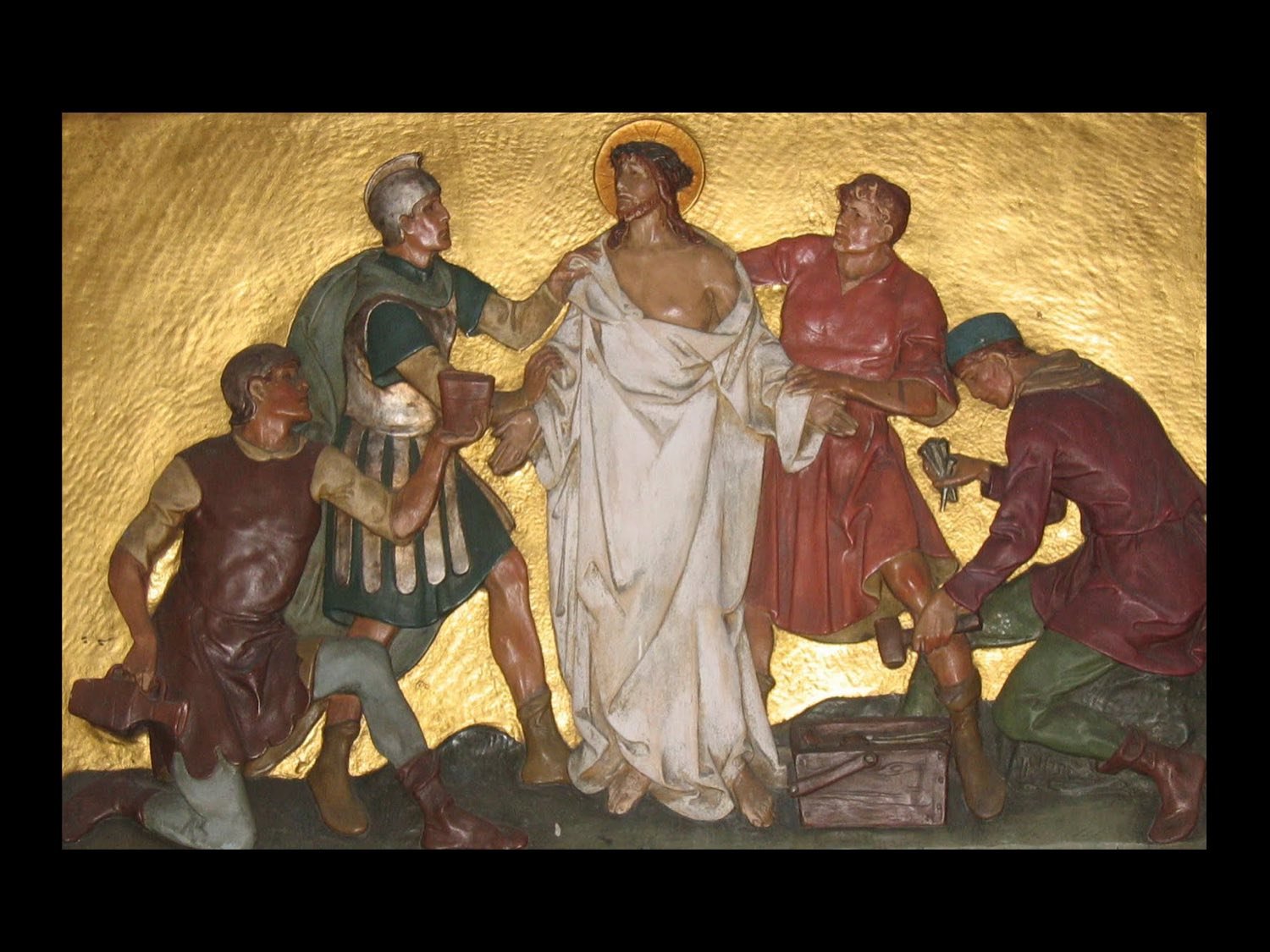

While the event described by this station is not stated explicitly in any of the gospels, it is clearly inferred that all of Jesus clothes were stripped from him before he was crucified, that is nailed to a cross. Here are some examples of art works that commonly depict this event...to be honest I find them sanitizing and misleading although presumably they were appropriate for their time...

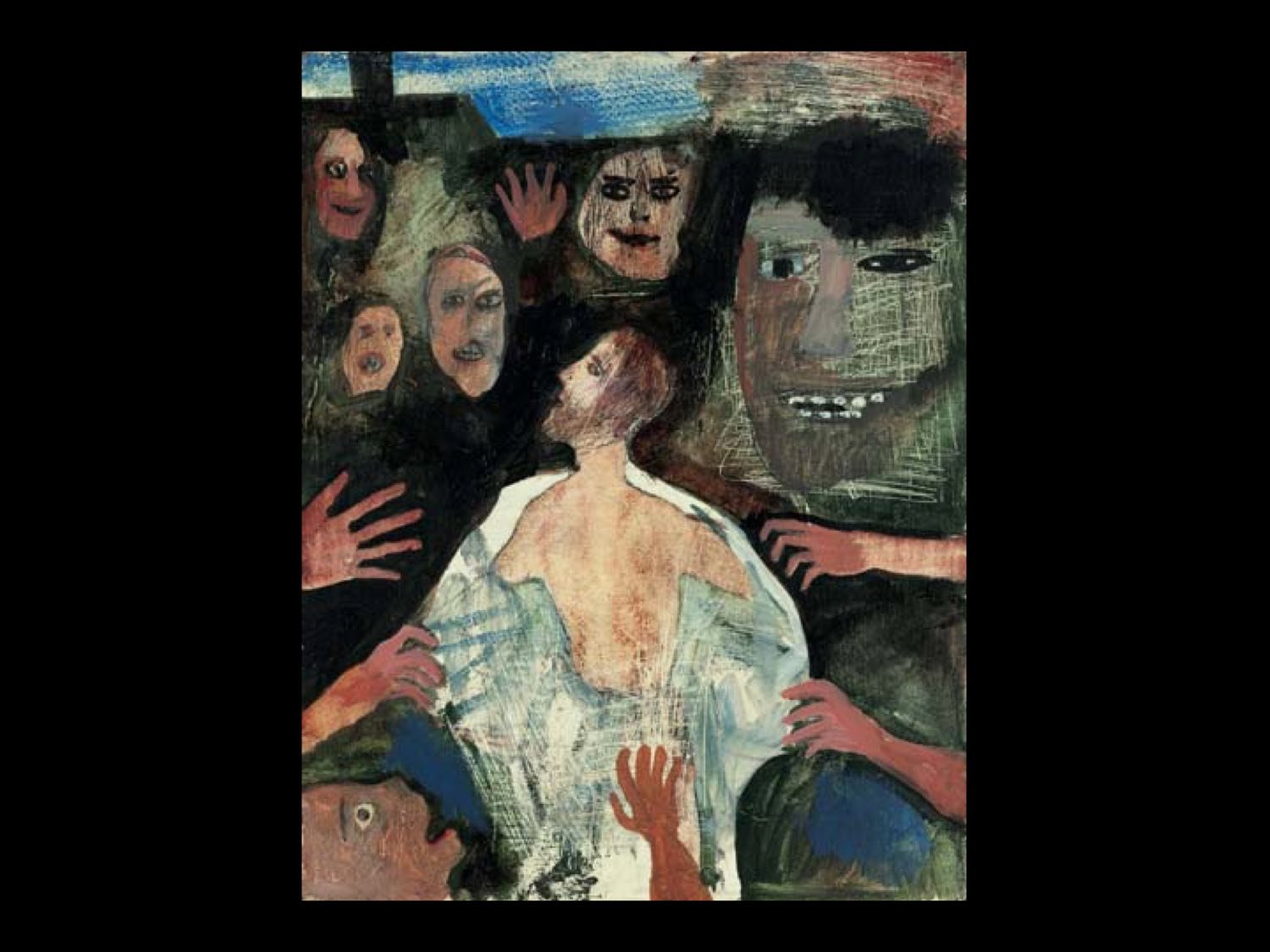

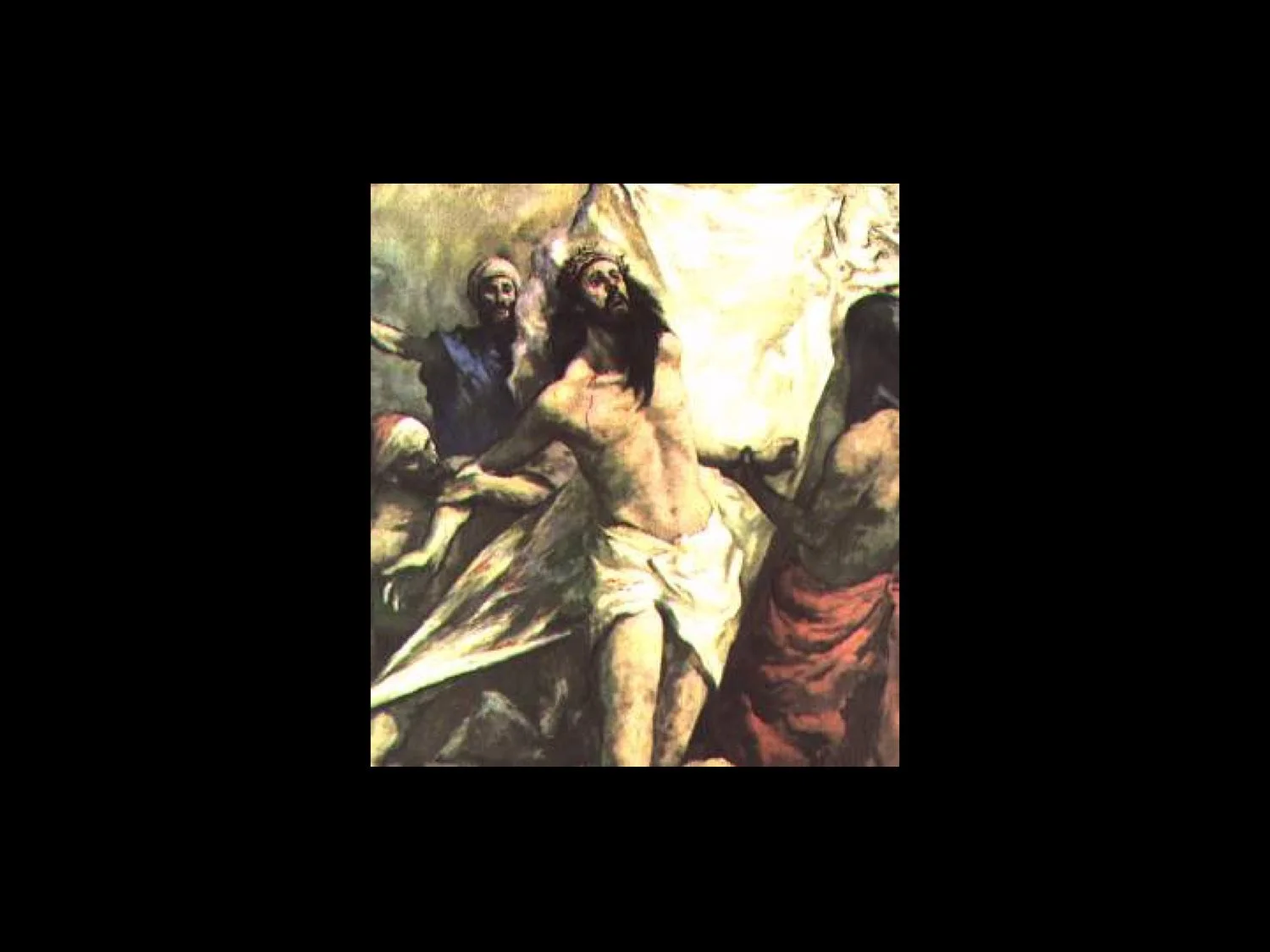

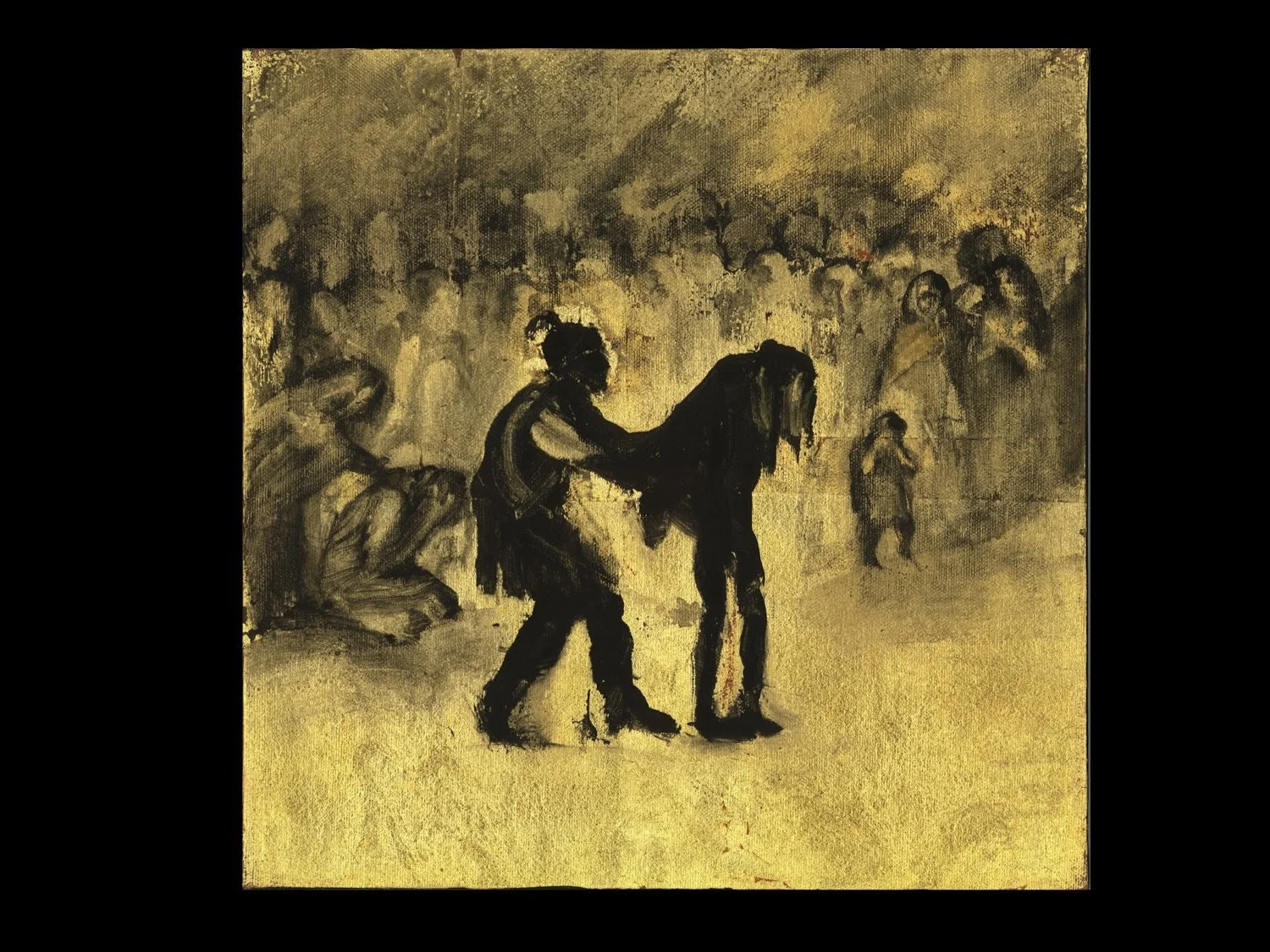

This next set come closer to what I believe was more likely to have happened...

It is important to remember Jesus was in fact stripped on three occasions on his journey to his crucifixion. We read again from earlier part of Mark chapter 15, after Jesus had been handed to be crucified:

Mark 15:16-20 The Soldiers Mock Jesus

16 Then the soldiers led him into the courtyard of the palace (that is, the governor’s headquarters and they called together the whole cohort. 17 And they clothed him in a purple cloak; (we read here that his own clothes were removed) and after twisting some thorns into a crown, they put it on him. 18 And they began saluting him, “Hail, King of the Jews!” 19 They struck his head with a reed, spat upon him, and knelt down in homage to him. 20 After mocking him, they stripped him (this is the second occurance) of the purple cloak and put his own clothes on him. Then they led him out to crucify him.

And as we are observing, he was stripped again as the soldiers began the crucifixion.

In her book The Power of Disorder: Ritual Elements in Mark’s Passion Narrative, Nicole Wilkinson Duran says that clothing embraces and expresses social identity, and like a ritual itself, clothing connects the body of the individual to the social body in which he or she dwells...[in that way clothing] has an informative function. Wherever they appear in Mark’s gospel, body coverings associate with social identity and ritual substitution.

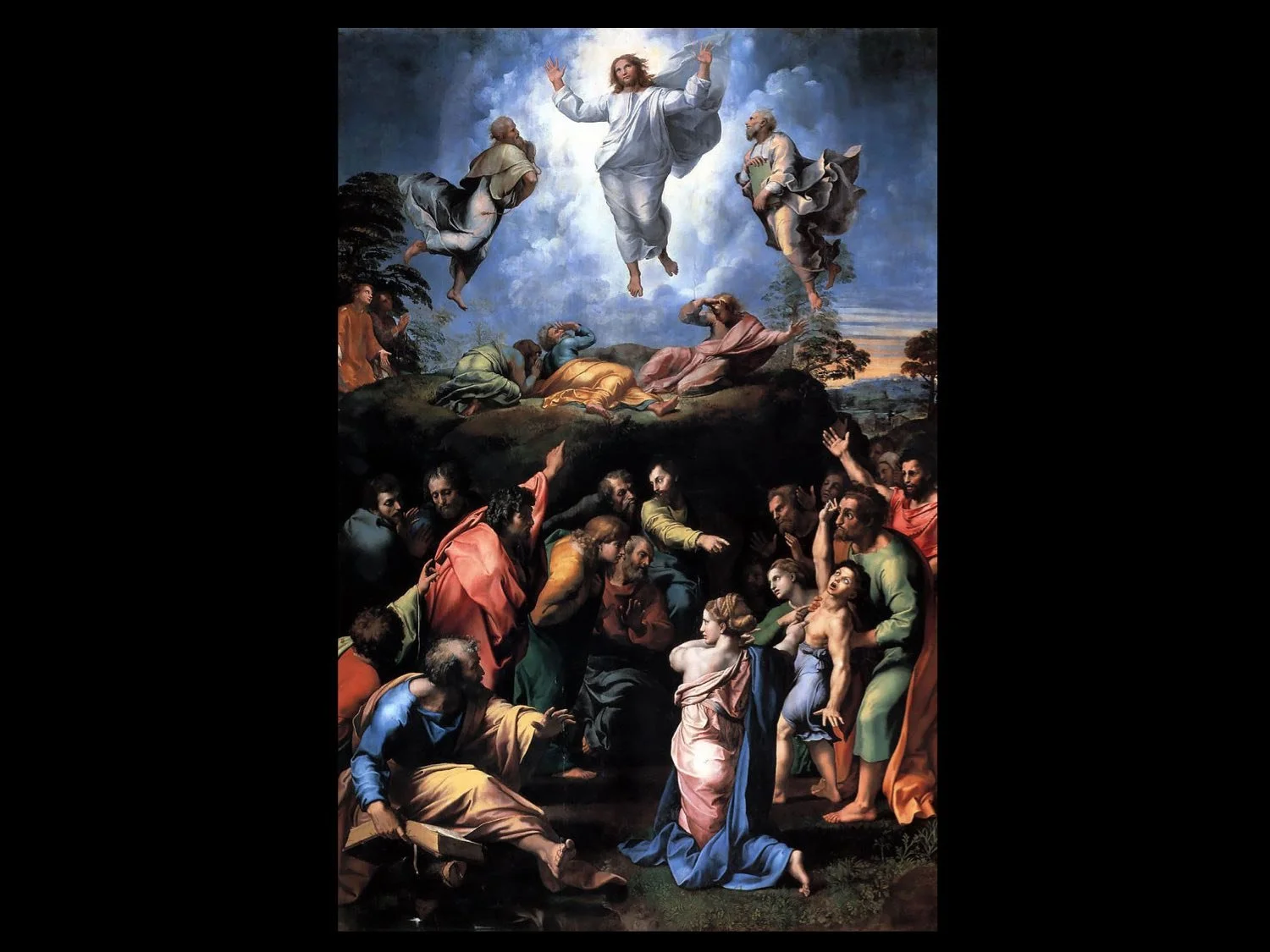

The Transfiguration

And so prior to his journey to the cross, and on another hill...then unnamed, but now referred to as the Mount of Transfiguration, we are have been presented with the revelation of the man Jesus as the Son of God. He is communing with the prophets. He is discussing important revelations, events to come, the high order of things. While in shining garments he is revealed as the Beloved Son...we read in Mark chapter 9...

Mark 9:2-13 The Transfiguration

Jesus took with him Peter and James and John, and led them up a high mountain apart, by themselves. And he was transfigured before them, 3 and his clothes became dazzling white, such as no one on earth could bleach them.4 And there appeared to them Elijah with Moses, who were talking with Jesus.5 Then Peter said to Jesus, “Rabbi,

it is good for us to be here; let us make three dwellings, one for you, one for Moses, and one for Elijah.” 6 He did not know what to say, for they were terrified. 7 Then a cloud overshadowed them, and from the cloud there came a voice, “This is my Son, the Beloved listen to him!”8 Suddenly when they looked around, they saw no one with them any more, but only Jesus.

Back to Golgotha)

On that other hill...the Beloved Son is stripped as we look on. And so we observe Jesus subjected to the fracturing of his social and spiritual identity, the violent removal of the fabric (literally and figuratively) that connected him to his “self in community”; while at the same being rendered naked, bared, exposed to public ridicule, shame, torment and humiliation.

I have been affected quite deeply by this topic, I felt disturbed and appalled at the indignity of the practice of public stripping as a instrument of torture...as a method of intentionally shaming, humiliating and dehumanizing. My feelings of being disturbed and appalled then gave way more intense feelings of horror and disgust as I’ve explored further the themes that swirl around this event. I’ve found that although I try to keep my head above the surface of it all there are stories and images and experiences that my mind has called up, events I have experienced as well as those close to me, events through history and in more recent times, events that have been experienced by individuals but also on a mass scale. Some of these events can be spoken of in a public setting, some cannot – for privacy and for emotional safety. These events and experiences mirror the weight of the emotional turmoil that Jesus’ public stripping will have had on him.

We have been conditioned to forget however. As the earlier paintings we saw showed, for every image we have seen of Jesus naked on the cross, we have seen 99 of him covered. But the fact is that Jesus died completely and obscenely naked.

There is a terrible tension between forgetting and observing. John Milbank, in his book “Being Reconciled”, explores the problems associated with our status as regular onlookers of scenes of violence, although we are removed from it as we live in a mostly post-violent society in comparison to the context of the crucifixion. As such, Milbank says that when we consume the artificial spectacle from the

comfort of our homes, and are lulled by the expectation of full termination, this circumstance results ultimately in a de- intensification of our being. There is no response required, except perhaps to be suitably horrified. Likewise, when we observe the past we tend to do so with a double passivity, we imagine that the violence is essentially over, and as such is frame-able by our gaze (perhaps as stations). We then do violence to the past, because we render it too different from our present, and we fail to sympathize with its dilemmas.

I don’t think you need me to tell you, however, that the violence is far from over, and if anything it has been increased by being abstracted and generalized. It is like the regularity of breathing that we do not notice.

Emotional safety...as an observer, for emotional safety I will move on, out of harms way, in a week or two. I’m conflicted, but what use is it to carry horror on my back like a weeping sore, who does it serve? But on the other hand we must remember, we know that intuitively...We must remember, but with caution, because what use is it to remember if we are not stirred to notice anew in the present, and to KNOW this violence as it breathes, and to NOT inhale or exhale it, and to NOT strip or be stripped.

Stanley Porter, in his book “Paul’s World” states that one of the KEY GOALS of crucifixion was humiliation and one of these methods revolves around sexual humiliation and assault. During crucifixion the victim would be stripped of his or her clothing and be hung up for all to see. This forced nakedness would be very shaming in Roman culture and especially so within the Jewish context considering their scruples against public nakedness. This aspect would only be compounded, as people would begin to lose control of their body and their ability to defend themselves (I won’t go into the details). Consequently, the soldiers could impose any form of humiliation on the person as they desired. As a result, the exploitation of extremely vulnerable people by Roman soldiers was an intricate component in the humiliation of the victim.

David Tombs, who is the Director of the Centre for Theology and Public Issues, at the University of Otago in his book “Crucifixion, State Terror, and Sexual Abuse” says that “based on what the Gospel texts themselves indicate the sexual element in the abuse is unavoidable.

An adult man was stripped naked for flogging, then dressed in a an insulting way to be mocked, struck, and spat at by a multitude of soldiers before being stripped again...and re-clothed for his journey through the city – already too weak to carry his own cross – only to be stripped again (a third time) and displayed to die whilst naked to a mocking crowd.”

For what use is it to remember this violence but to KNOW it as it breathes...

Stripped with dogs

Joseph Bathanti, poet laureate of North Carolina, from his 2012 recent collection “Sonnets of the Cross” responds to station number 10:

Hemorrhaging from the concertina

crown, brass knuckles, scourging, cigarette burns, lurching the last meter of Golgotha

where He must dangle three hours in urns

of japing ether, He drops His bloody tree. Executioners rip His clothes away,

cut cards for His keepsake convict jersey.

He's not uttered a word except to pray

for the spike drivers limbering their mauls

to fasten the scripture of agony.

He's ready for the juice, the black hood, spalls

of sniper fire, the hangman's ennui.

Naked upon the whorled slab he lay,

dreaming of the governor's last-second stay.

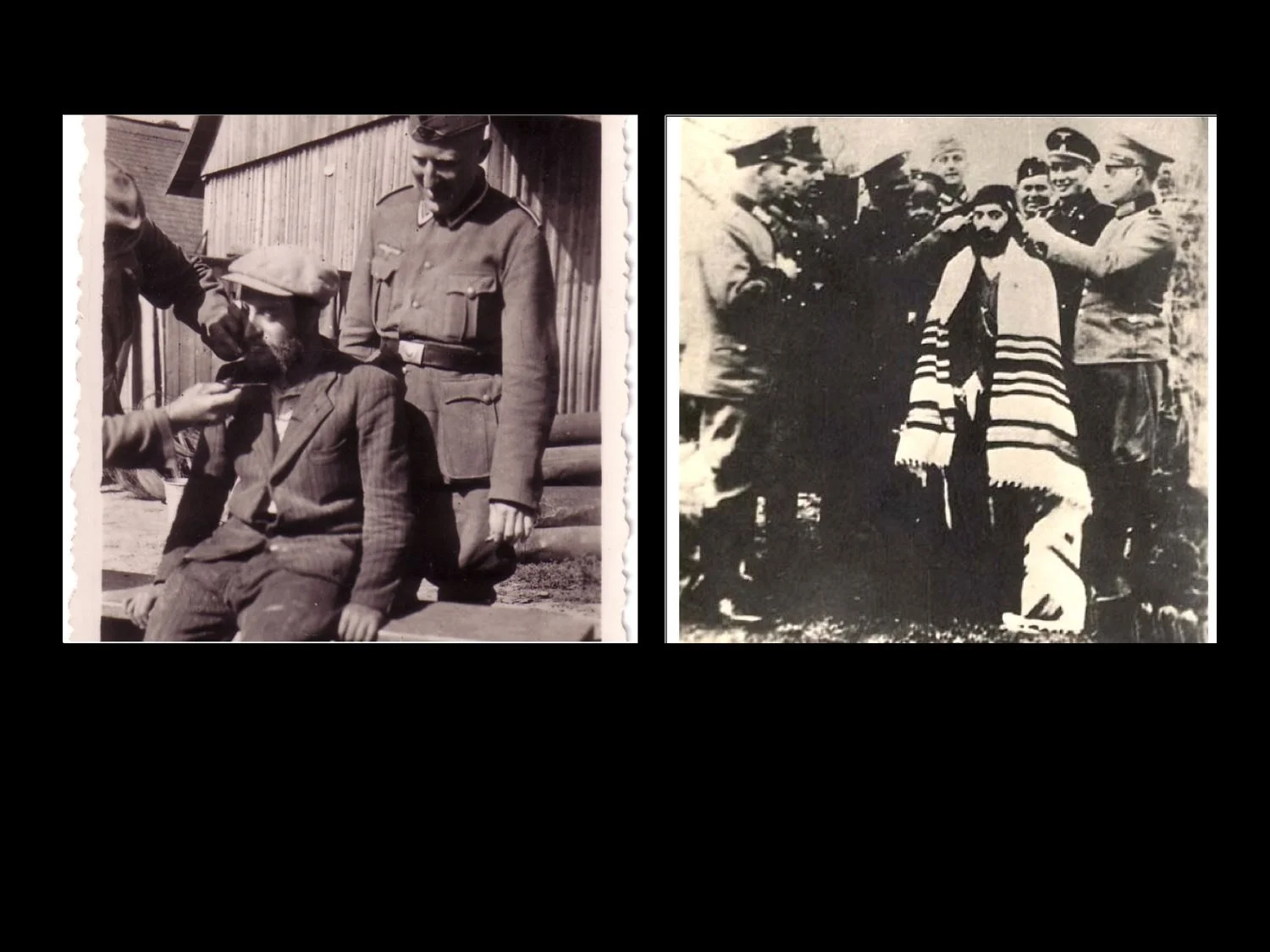

Holocaust

Joseph Cardinal Bernardin, who was the Archbishop of Chicago, in his book “The Journey to Peace” recalls a book of photographs called “The Holocaust” and shares some of his own reactions and reflections to one particular photo.

“It is not the most horrible picture, nor is it the most famous” and describes a photo of two men facing each other similar to these ones...

The Nazi soldier is cutting off the beard and earlocks of the Jew. The caption reads, “Shearing off or plucking out beard and earlocks of Orthodox Jews in front of jeering crowds was a favorite pastime in occupied Poland.”

Why does that picture remain in my mind? Wonders Bernardin. On the surface it is far more benign than the pictures of emaciated bodies lying strewn in a huge mass grave in the Nordhausen concentration camp. It is not as confronting as the eighteen faces staring from the wooden bunks at Buchenwald. It is not as gruesome as the skeletal remains outside the crematorium furnaces of Majdanek.

Why then does it stand out? Because it is so close to being ordinary. Because it is not so horrendous as to be totally alien to our own experience. Because it is within the realm of our own possibilities for cruelty.

So many of the perpetrators of the horrors of the Holocaust were banal, petty, mean-spirited, envious, cruel people. They were bullies who had extraordinary opportunity to act out their prejudices, their hatreds.

That is what we see in the picture. A bully who has power over another human being. A person who can transform a simple act that barbers perform daily into an act of humiliation and

desecration. How simple it is to cut someone’s hair! And yet what a violation of one’s dignity it can be. What a violation of a sacred way of life, a faith, a tradition, a commitment! A smirk on one face. Depth of pain, loss, humiliation on the other.

As we look at this scene, we realize that we are, at our worst moments, capable of similar actions. No, we could not starve people to death. No, we would not turn on a gas oven or crematorium. No, we could not shoot children in cold blood. But yes, we could humiliate another human person. Yes, we could smirk in enjoyment at someone else’s embarrassment. Yes, we could mock someone else’s cherished symbols of belief.

The child who taunts a classmate beyond endurance. The adult who tells jokes with racial, religious, or ethnic mockery. The superior who publicly berates an employee. These commonplace instances are not entirely alien to the banality, the petty cruelty, the meanness of spirit in that photograph of a Palestinian man, arrested, stripped and blindfolded at a Israeli border checkpoint, designed specifically to restrict Palestinian movement.

Chilean Christ

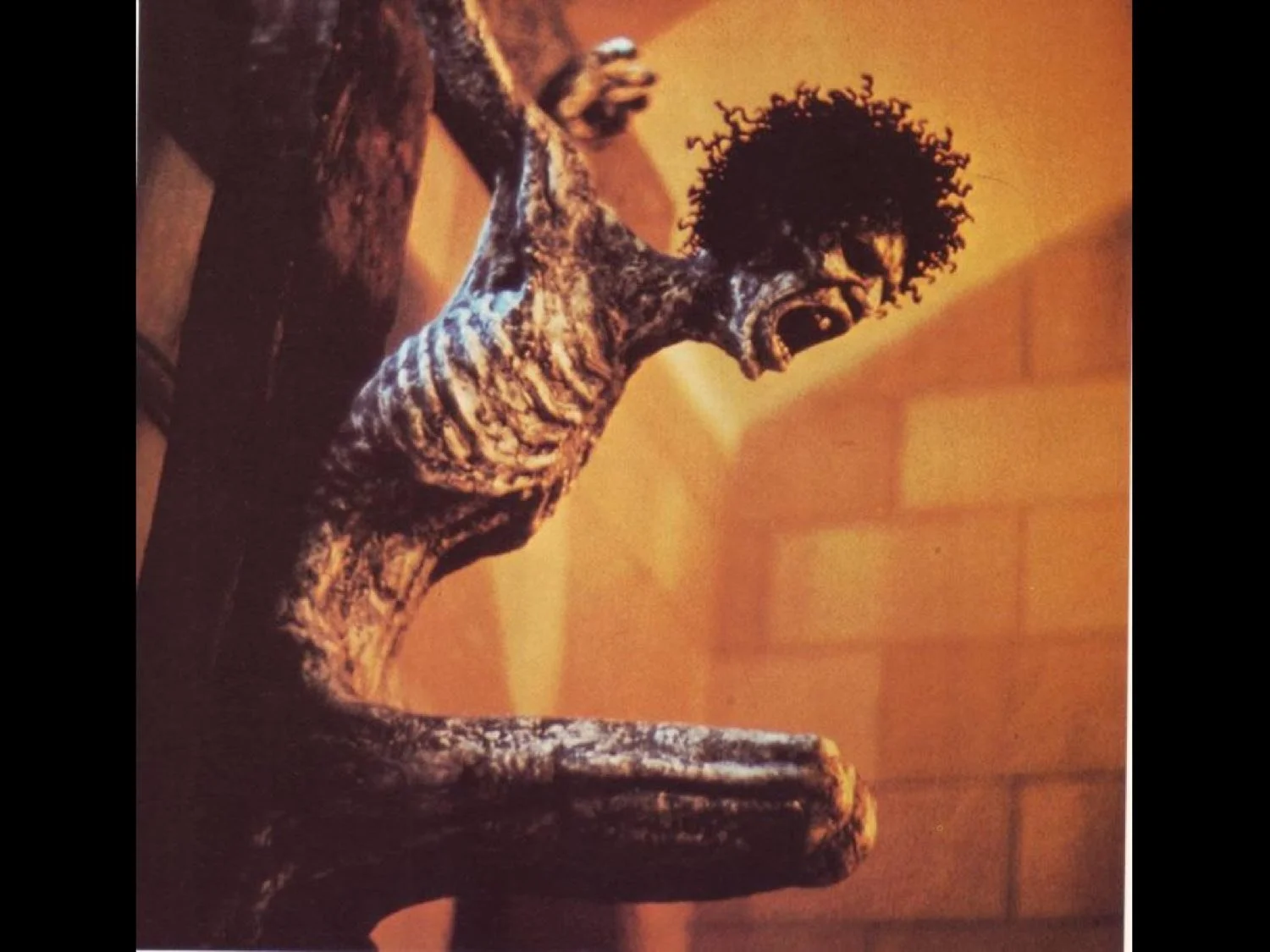

Brian Bantum, Associate Professor of Theology at Seattle Pacific University, who writes on matter of racial justice and reconciliation, has recently written this:

In the last year I have been pressed more and more to ask what do we Christians mean when we confess Christ. The seemingly never- ending news of people’s lives disregarded, murdered, criminalized is almost too much to take in. Trans, gay, lesbian, black, Muslim, women. Do we not worship a God who was desperately, unabashedly, scandalously FOR our bodied lives?

Today my Jesus is not a placid Jesus who quietly allows himself to be pinned to the cross taking punishment for transgressions of ideology or theological phantasms of right thinking. Today my Jesus is Brazilian sculptor, Guido Rocha’s Christ. One who identifies with the pain and suffering and totalizing terror of sin manifest in society’s structures. He is nailed to the cross for his opposition to terror and hate. He is nailed to the cross because his love is transgressive.

And upon that cross, his body pulls against the torment of society’s refusal of God, his emaciated and suffering body struggles against the evil that courses through creation’s veins. His screams of agony are mingled with a rage and anger that emanates from the verybeginning of time, that his creatures would kill and destroy and dehumanize one another so. This Jesus calls to me to struggle in my everyday, to not let a single muscle in my life not work against this tyranny. This Jesus calls me to a transgressive love and a perpetual call to confess, to make right, to speak truthfully.

Guido Rocha, the Brazlian sculpter, has said himself:

Today, increasingly, the so-called western Christian civilization sees itself faced with two Christs: the Christ of the oppressors and the Christ of the oppressed. The Christ of the oppressors is the one which submits, without struggle, to exploitation, absolves the sins of the torturers and threatens with hell the "laziness" of the undernourished peasant's son. For us, as artists of Latin America, the Christ of the oppressed is born in the soul of the people. His cry is a weapon of struggle, who creates out of his weakness the strength to struggle against the exploitation of man by man.

In Chacabuco, a concentration camp in the desert area of northern Chile, the following poem was written in 1974 by one of the political prisoners. Some Christian communities in Chile now use it as

prayer at the eucharist. I will read it in part...

HE SAID HE WAS A KING

The armed retinue was mocking

the one crowned with thorns,

they took off his rags

and beat his head with a cane.

Offensive mouths spat on the man

with the long hair, rebel eyes and unkempt beard.So, mocked by the soldiers

and with a mistreated body,

a bloodied man was dying

before the eyes of the high priests -

supreme hyprocrisy, supreme meaness and greed.Today I remember you, a freedom-loving Christ, vagabond in time, dubious in space.

Were you Spartacus' brother,

contemporary of the slave or comrade worker?What matters the chain, the fiefdom, the wage:

to be Nazarene or Chacabuco inmate

if you are on earth, brother Christ,

Son, with dirty face and calloused hands, flesh and blood of the people, lord of history at home with the plane and hammer,

a distinguished carpenter;

or with shovel, pick and pointed stick, a noble road builder...Eternal resident of the poor and barren hovel with roof of tin or stars, floor of sand or dirt, modest or captive walls.

You do not dwell in the oppressive mansion, the caves of thieves or the palace of Caesar.

The ingenuously pious fauthful swear they will find you in the fixed and shallow rite,

in the golden chalice and the simplistic devotion

of those who cry 'Lord, Lord'

but who, after going through the motions, do nothing.

(Attack on pacifist settlement at Parihaka)

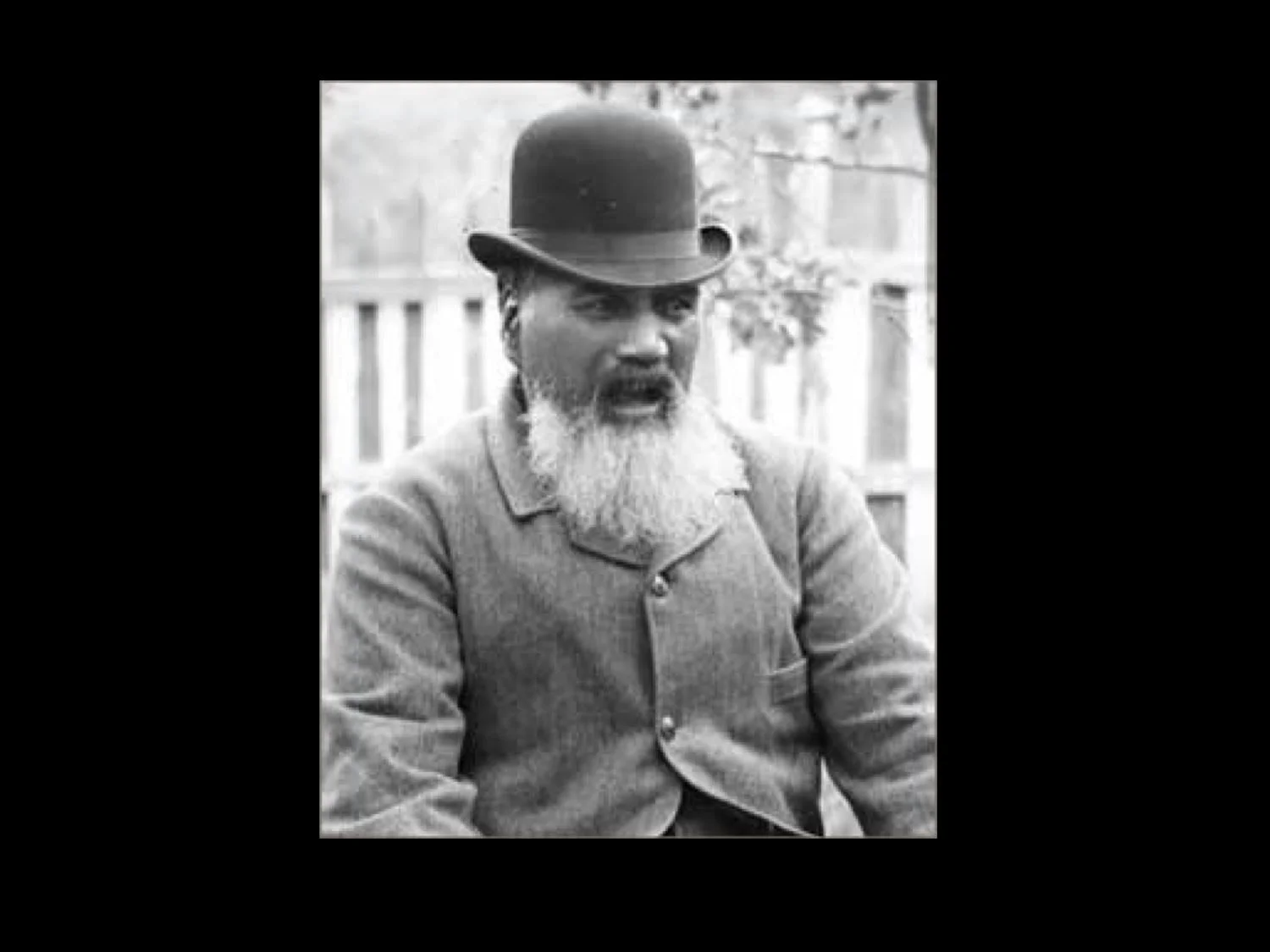

And here in Aotearoa we retell the events at Parihaka in 1881.

Parihaka was a settlement in western Taranaki which had at that time become the symbol of protest against the confiscation of Māori land. Its primary leaders were Te Whiti-o-Rongomai and Tohu Kākahi.

Te Whiti and Tohu employed tactics of non-violent non-cooperation in their struggle against land confiscations. The government responded to their protests by passing laws aimed specifically at the Parihaka protesters and ultimately by imprisoning people without trial.

Parihaka became of concern to the government as a possible site for the reignition of Māori opposition to Pākehā ‘progress’. As the historian Hazel Riseborough wrote: ‘Parihaka had become a haven for the dispossessed and disillusioned from the length and breadth of the coast, and as far away as North Auckland, the King Country, Wairarapa and the Chatham Islands.’

On the morning of the 5th of November 1881, some 1600 volunteer and Armed Constabulary troops invaded the settlement. More than 2000 villagers sat quietly on the marae as a group of singing children greeted the force led by Native Minister and Wanganui MP John Bryce, who had described Parihaka as ‘that headquarters of fanaticism and disaffection’. Bryce ordered the arrest of Parihaka’s leaders, the destruction of the village and the dispersal of most of its inhabitants.

The press, banned from the field by Bryce, were ambivalent about the government’s actions, but the great majority of colonists were reportedly in favour of them. Te Whiti and Tohu were detained without trial for 16 months. In the absence of its leaders, the Parihaka community no longer seemed to pose the threat that Bryce believed it had. The government also managed to delay for several years the publication in New Zealand of the official documents relating to these events.

This drawing of Te Whiti shows the Prophet of Parihaka walking over to the arresting-party of Armed Constabulary. He is wearing a korowai cloak of finely dressed and woven flax, the clothing of his younger days. At his trial in New Plymouth Te Whiti was charged with 'wickedly, maliciously, and seditiously contriving and intending to disturb the peace.'

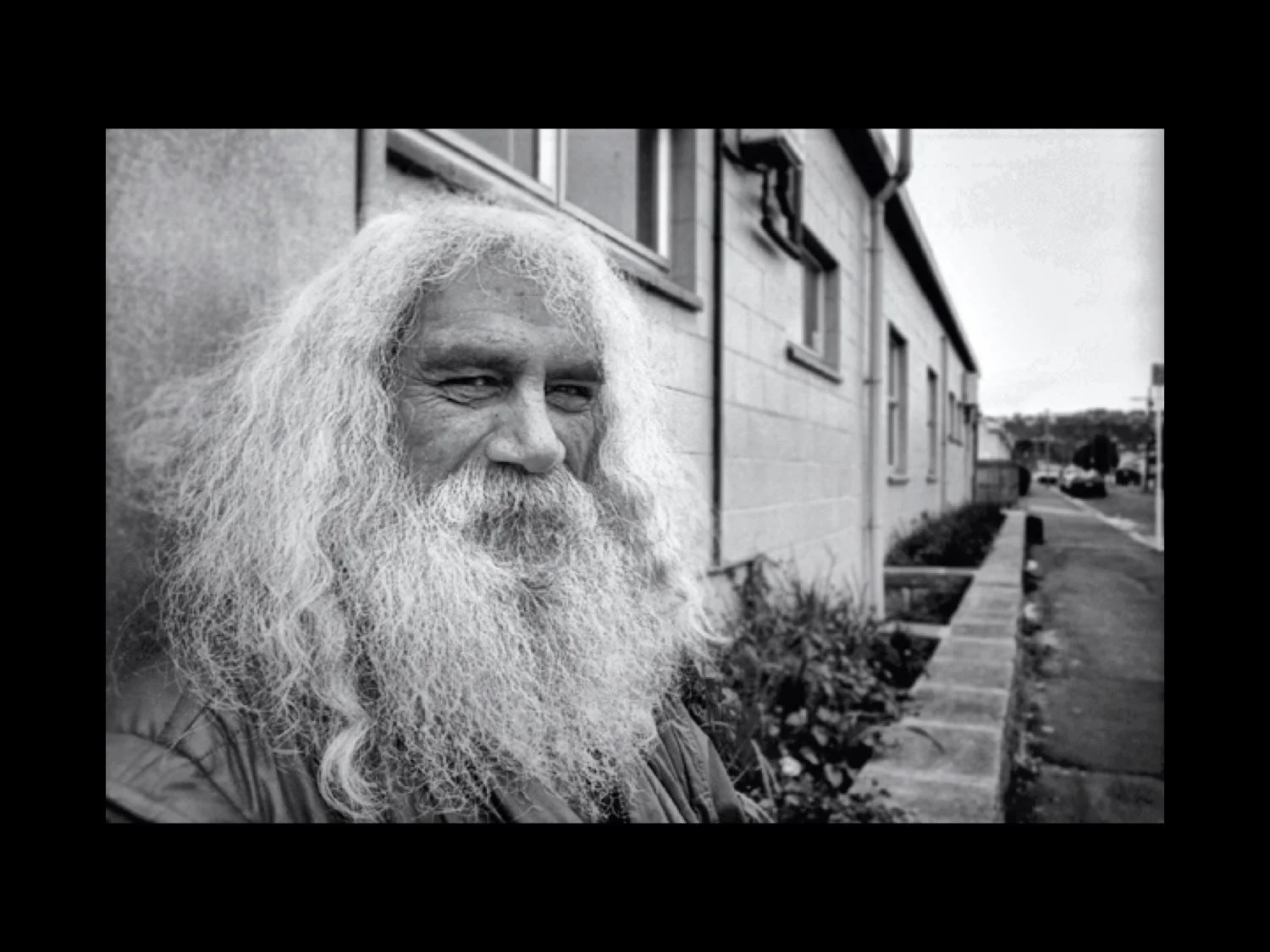

Some 80 years later, a pakeha man, who chose to call himself Hemi and moved Jerusalem (near Wanganui) to form a community centred on ‘spiritual aspects of Maori communal life’ wrote a poem called...

The Māori Jesus—James K. Baxter

I saw the Maori Jesus

Walking on Wellington Harbour.

He wore blue dungarees,

His beard and hair were long.

His breath smelled of mussels and paraoa. When he smiled it looked like the dawn.

When he broke wind the little fishes trembled. When he frowned the ground shook.

When he laughed everybody got drunk.The Maori Jesus came on shore

And picked out his twelve disciples.

One cleaned toilets in the railway station;

His hands were scrubbed red to get the shit out of the pores. One was a call-girl who turned it up for nothing.

One was a housewife who had forgotten the Pill

And stuck her TV set in the rubbish can.

One was a little office clerk

Who'd tried to set fire to the Government Buldings.

Yes, and there were several others;

One was a sad old quean;

One was an alcoholic priest

Going slowly mad in a respectable parish.The Maori Jesus said, 'Man,

From now on the sun will shine.'

He did no miracles;

He played the guitar sitting on the ground.The first day he was arrested

For having no lawful means of support.

The second day he was beaten up by the cops For telling a dee his house was not in order.

The third day he was charged with being a Maori And given a month in Mt Crawford.

The fourth day he was sent to Porirua

For telling a screw the sun would stop rising. The fifth day lasted seven years

While he worked in the Asylum laundry

Never out of the steam.

The sixth day he told the head doctor,

'I am the Light in the Void;

I am who I am.'

The seventh day he was lobotomised; The brain of God was cut in half.On the eighth day the sun did not rise.

It did not rise the day after.

God was neither alive nor dead.

The darkness of the Void,

Mountainous, mile-deep, civilised darkness Sat on the earth from then till now.

If we are to remember we cannot do so for our own sanctification. To be horrified is not redemptive. It does not make us holy. Our worship is not more valuable. To be emotionally wrought does not, in itself, restore. But when we have observed, we have become accountable for our response. We are to acknowledge, in ourselves, in our oppressors, in our institutions, in our churches acts of shaming, making lowly, dehumanizing the other and to KNOW it as it breathes.

And in doing so we open the way to re-clothe

For have mercy is better than sacrifice, as we are told in Hosea 6.6 and as repeated by Jesus on more than one occasion.

Is it possible, then, that we can participate in the re-clothing of Jesus, as was done lovingly in his burial, mystically in his resurrection and majestically in his ascension. How can we imagine him re-clothed in our communities, how are we to join with him in this project of restoration?

As I’ve spent time in this seromn I’ve been reminded of many good projects and people who work to clothe the one or the many who have been stripped of their identity, their honour, their diginity.

I want to tell you about one such project, mostly because I know it well through Jared, my husband. Adventure Specialties works in conjunction with CYFs and Man Alive (a counseling service for men and boys) to facilitate a programme for young men, boys to be accurate, who have either been court ordered to attend the programme or have agreed to attend as the result of a family group conference. These boys have the choice of either incarceration in one of our Youth Correctional Facilities or complete the programme which is called Te Wero Aki.

Te Wero Aki means “The great challenge” and using restorative philosophies it invites the boys to discover their true selves by overcoming significant challenges, physically, emotionally and relationally, as they journey through the wilderness. Now, we are not exemplary people, we have found ourselves with the opportunity to offer ourselves in such a way.

During the programme the boys are asked to spend time observing and noting down the things they appreciate about each other. At the end of the programme they are reunited with their family members and a celebration meal is held. After the meal, each boy is invited to sit at the front of the room and turn by turn the other boys and staff who were on the programme read a statement of encouragement about the boy. Something that is known to be true, that has been observed. The statement, which has been pre-printed on a sticky label, is then stuck onto the boy, covering him in dignity and honour.

This act of “clothing” the criminal in layers and layers of goodness, goodness that IS re-identifying them by what has been observed as the essence of their true self. Because it is most likely that whatever goodness these boys had at one time been aware of in themselves, this goodness had mostly been stripped from them as a result of the conditions of their environment in which they have emerged. Clearly the resulting behavioural responses that they engaged in sealed their fate, limiting and further limiting the prospect of an matured responsible citizen.

And so once they have been clothed in their sticky new, true identities, and they are able to stand in dignity. They read a letter they have written to their families. They express regret, they explain, they apologize, they share grief, they offer forgiveness, they make promises and they make known their deep love for their family members.

And now the family members, also able to stand dignified, although timid, offer the same in return, if they can, to their boy who can barely raise his eyes under the weight of the honour he is recieving. I’ve had the opportunity to observe a couple of these events and its as though the Kingdom of God is being revealed.

These are tough boys. Boys who have done bad things. Things they can’t take back. Yet in this moment clothed in righteousness, as it were. Lovingly, mystically and majestically restored...while in part, however. Of course, it’s a journey.

You may remember the movie “Blood Diamond”. The title refers to diamonds mined in war zones and sold to finance conflicts, thereby profiting warlords and diamond companies across the world. Girls and boys illegally and under force, participate in combat where often they are injured or killed. Others are used as spies, messengers, porters and servants. Child soldiers are robbed of their childhood, their education, and a stable environment and are exposed to terrible dangers and suffering due to the atrocities they are required to engage in.

In this movie, one of the main characters, Solomon Vandy, is confronted by a boy who appears to be prepared to kill him. It turns out to be his son and in a beautiful, harrowing display of re-clothing the father says:

Dia, What are you doing? Dia! Look at me, look at me. What are you doing? You are Dia Vandy, of the proud Mende tribe. You are a good boy who loves soccer and school. Your mother loves you so much. She waits by the fire making plantains, and red palm oil stew with your sister N'Yanda and the new baby. The cows wait for you. And Babu, the wild dog who minds no one but you. I know they made you do bad things, but you are not a bad boy. I am your father who loves you. And you will come home with me and be my son again.

I have other examples or re-clothing that I could offer, past and present, my own stories, stories of those I know, stories of Syrian Refugees, Nigerian School girls, Alzheimers sufferers...but I also know that as a community we are very engaged in this type of restoration.

So if collectively remembering, observing, Jesus being stripped of his garments calls us again to notice and acknowledge the ongoing humiliating, shaming, and dehumanizing effects of this type of violence, as it occurs in it’s many forms in our communities...to notice it as it breathes – we must also name the acts or practices of re-clothing that are already occurring so that we can support and participate in God’s project of restoration. I have asked a couple of people to tell about specific projects they have been involved in that offer a “re-clothing” of a person or group of people.